The Cold Spring Park Pollinator Garden

Come visit our new pollinator garden of native wildflowers–the first in Newton designed to support specific bumblebees and butterflies at risk of local extinction–right at the park entrance on the knoll between the driveway and tennis courts!

The highly visible site is perfect for a demonstration garden. Everyone entering the park from Beacon St. will see it. It is also right next to the weekly Farmers’ Market, enabling us to give in-person explanations and hand out information about the garden on market days next year.

The garden in June 2023.

Making the garden

The garden was planted on October 10, 2022, after months of detailed planning. The Department of Parks, Recreation, & Culture (PRC) approved the plans and helped choose and outline the site, remove the sod, and provide a water trailer. For his Eagle Scout project, DoBi Wollaber, of Scout Troop 209, helped plan and design the garden along with the Friends of Cold Spring Park. Dobi and his family and scout troop, along with Friends volunteers, did the planting, with funding provided by the Friends, with help from grants from Green Newton and Newton Conservators. Read more about the making of the garden….

Cute short video of the garden installation, by Jon Goldberg.

Volunteer to help with garden maintenance and new plantings!

Why a pollinator garden?

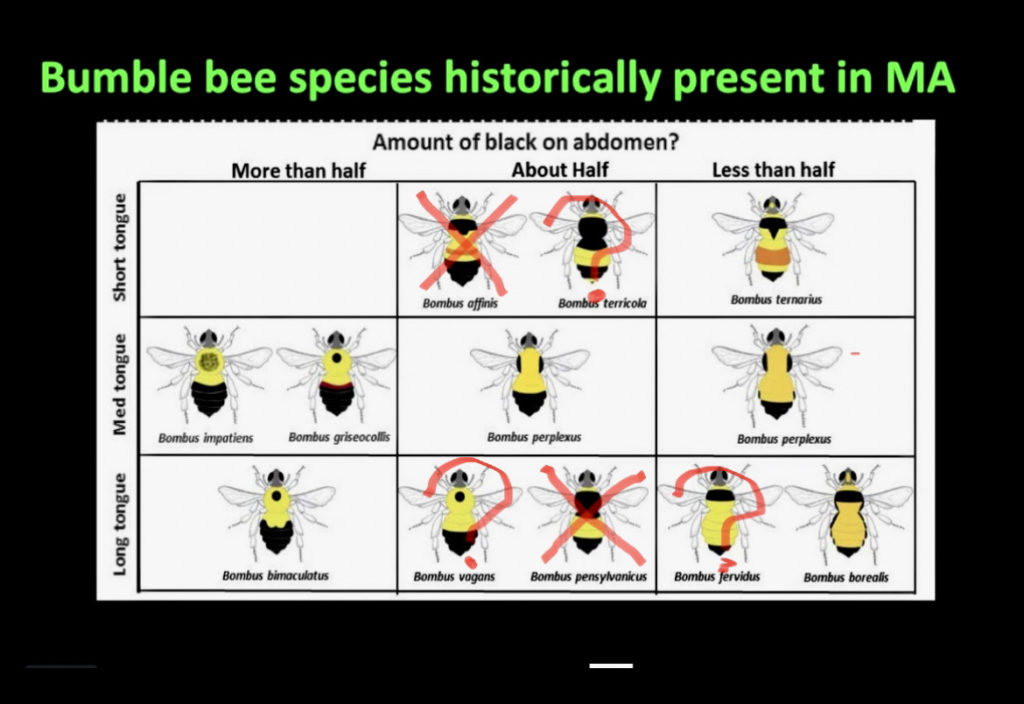

The garden aims not only to beautify the park’s entrance but to help restore wildflowers and save bees and butterflies indigenous to our region. In particular, this is the first public garden in Newton intended to help save two species of bees–the golden northern (Bombus fervidus, pictured) and half-black (Bombus vagans) bumblebees–that used to be common in eastern Massachusetts but are now at risk of local extinction, based on the research of UMass Dartmouth Professor Robert Gegear. It will also help support ten species of at-risk butterflies.

The two bumblebee species at-risk in Eastern Massachusetts are both long-tongued bees. The garden includes many flowers with tubular shapes because those are preferred by and most easily accessed by long-tongued bumblebees.

Read more about the bees and butterflies the garden will support….

Plants and their pollinators depend on each other to survive. More than 85 percent of all plants require animals, especially insects, for pollination, a process essential for creating seeds and fruits and reproduction. At the same time, many pollinators develop specialized relationships that depend on specific plants. You may have heard, for example, that monarch butterfly caterpillars can only survive on milkweeds.

Sadly, many pollinators are in steep decline due to habitat loss, the use of pesticides and herbicides, and climate change. Habitat loss– from development, agriculture, and the spread of exotic and invasive species–robs pollinators of the native plants they depend on, and of their nesting sites.

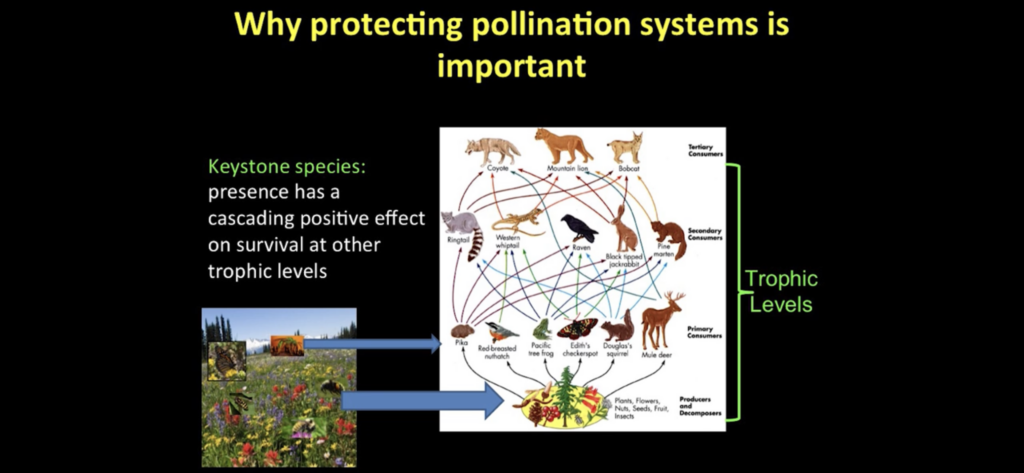

These communities of plants and their pollinators are keystones in the food web that supports all the wildlife around us, and our own food supply. Their loss contributes to a global biodiversity crisis, in which one million species–one-quarter of those alive today–are on a path toward extinction in the coming decades if we do not change course.

Why focus on bumblebees?

Bees, in general, and bumblebees in particular, are the most important pollinators in our natural environment. They pollinate many important crops (e.g., tomatoes, squash, blueberries, and cranberries) as well as our indigenous ecosystem. While some bumblebees, like the common eastern bumblebee, are thriving, other species are in decline. Scientists have found that having a diversity of species is necessary to maximize crop yields and maintain the health and resilience of the ecosystem.

In Massachusetts, we have already lost two of twelve indigenous bumblebee species, with three more at risk of local extinction within the next ten years. More than 40 butterfly species are also listed as of conservation concern in Massachusetts.

Unlike honeybees that live in huge colonies, our native bees are mostly solitary or live in small social groups. They are gentle, and will almost never sting unless you are threatening a nest. You can even pet a bumblebee (but don’t; they don’t really like it and will wave a middle leg to ward you off).

Massachusetts has almost 400 native bee species, most of which nest in the ground. Some 30-40 percent of them are thought to be in decline, but very little research has been done on most of them. They are difficult to research because most are small; some species can only be positively identified under a microscope! Bumblebees are much easier to identify and study. But the garden will help support many other native species as well. Read more about the bees and butterflies the garden will support. …

You can help pollinators in your own yard and garden

We hope the Cold Spring Park pollinator garden inspires you to help pollinators by planting some of these and other native flowers and grasses in your own yards and gardens. If enough of us do so, we can create “pollinator pathways” across Newton that also connect to the many other communities that are also undertaking such projects. What can we all do?

- Plant native plants, especially straight species (no ‘single quotes’ in the name). Read about our specific garden plants, garden design, and where we acquired the plants…

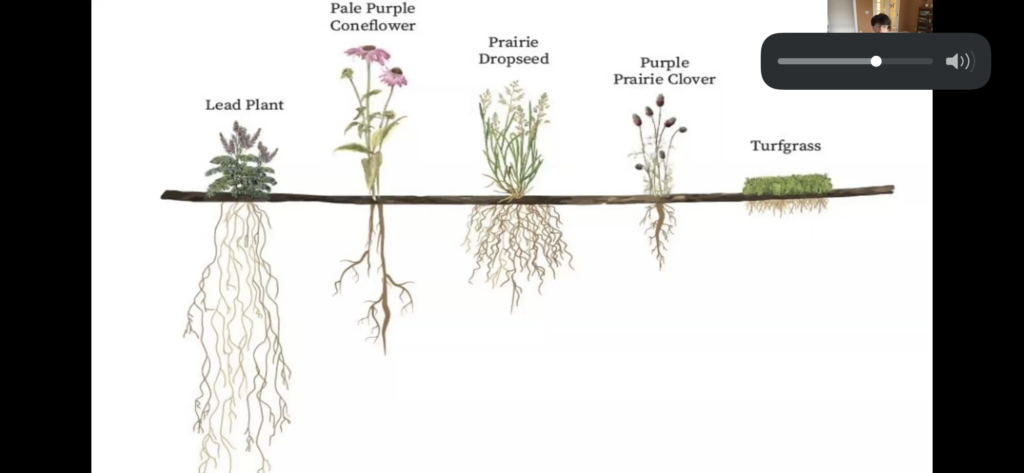

- Reduce your lawn area. Turf grass provides no resources for our native pollinators.

- Avoid chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, which can harm pollinators.

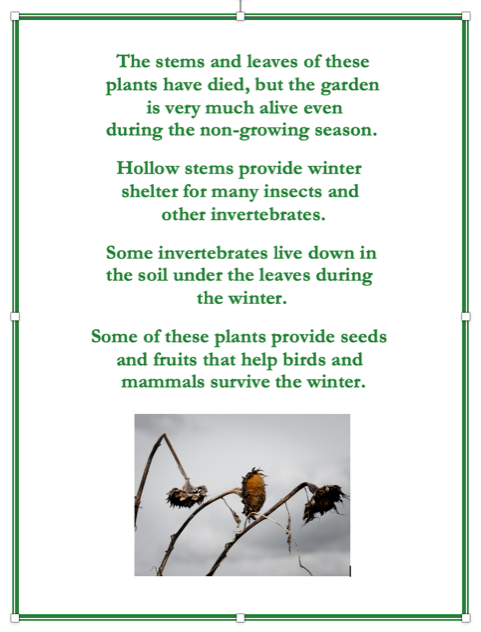

- Leave the leaves in your garden area, and don’t cut down stems before spring. Beneficial insects, including fireflies and many pollinators, nest in leaf litter and hollow stems. (As per the sign at the Newton Community Pollinator Project City Hall demonstration garden, pictured.)

It will take a few years for our garden to fill in, but once it gets going, we hope to be able to give away seeds in the fall to people who want to plant them in their own gardens and possibly have a plant sale in the spring for seeds we have germinated over the winter.

Many groups in Massachusetts and around the country are working on native plant pollinator gardens. In the resources section at the end, you will find links to other Newton, regional, statewide, and national groups and resources.

Read about our specific garden plants, garden design, and where we acquired the plants…

Other benefits of native plants

Like all perennial plants, native plants require regular watering and weeding to get established. But once they do, if you have chosen species that fit with your site’s sun and soil conditions, they will require much less water, no chemical fertilizers, and less maintenance than traditional gardens.

Because they generally have deeper roots, especially compared to turf grass, a native plant garden also retains more stormwater and stores more carbon. They help reduce flooding and make our ecosystem more resilient to climate change.

You will be amazed at the amount and variety of life your native garden will attract! “Build it and they will come.” Teach your kids about plants, pollination, bees, butterflies, biodiversity, and bugs of all kinds right in your yard!

What about honeybees?

Honeybees are not native to North America. They were imported from Europe by the colonists in the 1600s to provide honey, wax for candles, and crop pollination. They are still important for agriculture, especially for pollinating the large number of non-native crops we cultivate on large industrial farms. They are classified as livestock animals by the USDA.

Honeybees are not endangered. Honeybees live in hives of 50,000 or so bees, and are susceptible to parasites, pathogens and disease. Beekeepers in the U.S. tend to lose about one-quarter of their bees each winter, and import new ones from China and other countries. There are more honeybees alive today than ever!

Honeybees can even compete with native bees for limited supplies of nectar and pollen, especially In early spring, late fall, and during droughts, or when the density of hives in an area is too large. Honeybees can also transmit diseases to native bees when they share flowers. For these reasons, a consensus of scientists recommends that beekeepers avoid parks and other natural areas as a precautionary measure, while they continue to study these issues. Of course, we also cannot keep them out, as they can fly for miles to find food.

Watch Dr. Gegear on honeybees…

More resources:

Dr. Gegear’s plant list for at-risk pollinators

Evan Abramson sample designs/toolkits – specifically using Dr. Gegear plantlist

Newton Community Pollinator Project – Facebook page

Newton Conservators Pollinator Toolkit – more great explanations & resources.

Mystic-Charles Pollinator Pathway Group – Regional group for Mystic and Charles River Watersheds. Put your native garden on a regional map. Facebook page, monthly meetings with guest speakers. Garden tours.

Massachusetts Pollinator Network – Statewide network. Action alerts, resources, monthly meetings with guest speakers.

GrowNative Massachusetts – speaker series, annual plant sale.

Native Plant Trust – Garden in the Woods, Framingham. Classes, trainings, plant sales.

Dr. Doug Tallamy Homegrown National Park – National movement to create native plant gardens. Put your garden on a national map.

The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Research, webinars, advocacy.

A few great webinars:

Dr. Gegear on solutions for at-risk pollinators

Evan Abramson on Designing Biodiversity

Dr. Doug Tallamy on Pollinators’ Best Hope [You]

Nick Dorian, Tufts Pollinator Initiative, on The Secret Life of Wild Bees

Sam Droege and Jenan El-Hifnawi on creative pollinator programs around the world

Visit other Newton Pollinator Gardens:

- City Hall

- Wellington Park

- Kennard Park

- Newton South High School

- Dolan Pond

- Newton Cemetary